America's first missionaries reported to the Pope. Their work took them through Mexico and the American southwest as well as into Canada. They were tireless in their efforts to take a Christian message to Indian populations.

No English missionaries ever arrived. English evangelism occurred through colonization and expansion. Various religious groups arrived at different times settling in different areas. Once settled, these colonists reached out within those areas.

This document surveys Anglicanism's growth in early colonial settlements, particularly in Virginia.

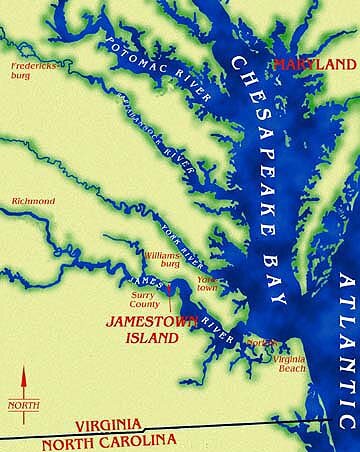

I. The Jamestown Settlement

Virginia's first permanent settlers arrived in 1607. They numbered about 105 but the colony soon grew to 500. Jamestown operated under the oversight of the Virginia Company, a private stock company which intended to establish a profit making colony to produce wealth for the shareholders. In England, James I worked at making the average Puritan miserable so the company limited the colonists to good Anglicans. A month after landing Robert Hunt led the colonists in their first American communion service. Within the year the colonists constructed a church building but fire destroyed it shortly after.

Virginia's first permanent settlers arrived in 1607. They numbered about 105 but the colony soon grew to 500. Jamestown operated under the oversight of the Virginia Company, a private stock company which intended to establish a profit making colony to produce wealth for the shareholders. In England, James I worked at making the average Puritan miserable so the company limited the colonists to good Anglicans. A month after landing Robert Hunt led the colonists in their first American communion service. Within the year the colonists constructed a church building but fire destroyed it shortly after.

Many colonists had no preparation for the difficulties of colonial life. Some had no manual skills and some spent their time looking for gold. Within six months 51 of the original 105 died. Statistics show that over a fifteen year period 50 percent of all colonists in Virginia died.

The colony's original charter called for governing bodies in Virginia and in England. In 1609 the company dissolved Virginia's governing body and appointed a governor in its place. Lord De La Warre, Virginia's first governor, remained in England but sent Thomas Gates to serve as his American deputy. When Gates arrived only 60 out of a total of 500 remained. Gates brought with him a new charter which required all colonists to take the "Oath of Supremacy." Affirmation of this oath meant excluding Roman Catholics from the colony.

In 1611 a new deputy governor arrived and with him came Alexander Whitacre, a clergyman who later wore the title "Apostle of Virginia." History describes Whitacre as a zealous evangelist and preacher. By 1611 the Virginia colony showed signs of permanence. Population growth and economic growth revealed that the colony made headway. John Rolfe completed his tobacco experiments in 1612 and gave the colony its economic stability. Colonists moved up the James River to establish new plantations and towns. When this happened, Whitacre moved upriver establishing churches. Whitacre really cared about the colony's spiritual welfare but he drowned in the James River in 1617.

II. The Development of "Home Rule"

Two important developments occurred in 1619. Virginia experienced a resurgence of local involvement in government and black slaves entered the colony.

Lord De La Warre's death in 1619 signaled a governmental policy change. The Virginia Company gave Virginia more self-rule in an attempt to encourage immigration and local development. Virginia towns, known as "burgs," send representatives to a colonial legislature. These "burgesses," or representatives, formed Virginia's House of Burgesses.

At the House of Burgesses' first meeting the assembly spent much time discussing the relation of church and state. Fully half of the laws enacted dealt with church matters. They enacted penalties for failure to attend worship or making derogatory remarks about ministers. In 1621, the House met to set salary standards for the clergy: 1500 lbs. of tobacco and 16 barrels of corn (mostly likely the liquid kind).

In 1619 a Dutch ship sailed up the James with 20 blacks on board. The Dutch hoped to find buyers in spite of the fact that the English discouraged black slavery in America. Black slavery had existed in English Caribbean colonies for some time, particularly in Jamaica. In spite of the discouragement, the Dutch sold their cargo and moved on. Within 30 years about 800 slaves worked tobacco and indigo crops and the number expanded dramatically in just a few more years.

By 1620 the colony seemed quite successful. Colonists had established profitable plantations up the James and economic growth brought in substantial returns. Virginians discovered precious ores and mining began. The Virginians raised funds for the colony's first college at Henrico upriver on the James.

The colonists enjoyed friendly relationships with the Indians led by Powhatan but Powhatan died in 1621 and his brother succeeded him. Powhatan's brother saw the white man's incursion as a definite threat. In March 1622, the Indians attacked upriver settlements virtually wiping out some of them. On March 22, 1622, Indians slaughtered at least 347 settlers which eliminated, in "one fell swoop," about 25 percent of Virginia's population.

Whites grew suspicious of the Indians. Talk of conversion ceased. The white man saw the red man as a devil! Planters abandoned some of the most distant Plantations and moved back downriver to establish more defensible borders. They shelved the dream of a college, closed the mines, and retreated. Soon after, the colony underwent a complete economic retrenchment causing losses to the Virginia Company's English stockholders. By 1624, both Virginia and the Virginia Company were bankrupt. The king canceled the charter and placed the colony directly under his supervision.

Virginia became a royal colony and remained such until the American revolution. The king confirmed Anglicanism as Virginia's state church operating under the colony's governor. Problems immediately cropped up. Under the Virginia Company's oversight, the company's directors demonstrated concern for the colony's religious life. With it's shift to royal status that concern stopped. The king appointed ministers but most of these appointments were incompetents. Then, too, Americans could not replace these appointments with Americans. Under Episcopalian polity only bishops ordain. America had no bishops. Virginia depended totally on England for its clergy. Many ministers who arrived in Virginia were misfits; those who couldn't make it in England.

III. The Formation of the Vestry

Virginians soon grew weary of English incompetents in their pulpits. They eventually took matters in their own hands and simply failed to inform England of vacancies. Anglican churches could and did survive without ordained clergy by relying on "readers" who directed worship. Although the church couldn't baptize or conduct communion services, they could still worship. American churches would rather do without some services to avoid English misfits.

Many Anglican churches appointed a board of 12 congregationally selected men to act as trustees. This board then selected the readers. As their power grew, they nominated and presented new preachers to the Virginia governor for approval. This is the vestry and gradually it's power expanded. Since they called ministers to one congregation for life, the vestry tended to be extremely careful. Vestries discovered that, while the state set the basic salary requirements for ministers, they could pay an interim minister whatever they deemed proper. The vestry could appoint a reader pay them a pittance. The state of the Virginia church depended entirely on the quality of its vestry. A good vestry selected ministers carefully. Others simply chose men from convenience or careless choice.

Historians see the vestry system as the beginning of American republicanism. In some ways that's true. The vestry often served as a training ground for representatives to the House of Burgesses.

Anglicanism suffered one major casualty in America--the parish system. Most European church structures still operate on that system. Anglicanism established parishes in early Virginia but geography doomed it. Virginia has too many rivers. Virginia's population spread out along these streams making pastoral work impossible. One Virginia parish was 10 x 120 miles and the average parish usually extended 25 miles in length. Colonists could hardly attend church at the one congregation allowed within the parish and visitation became impractical. The parish system's failure opened the door for other religious groups to enter Virginia later.

IV. Effects of the English Revolution

During the English Civil War Virginia's politics and religious life were chaotic. Little law and order existed in the colony and England was too preoccupied to help.

When England "restored" Charles II changes occurred. Henry Compton, the Bishop of Lincoln and responsible for the Virginia colony, took a genuine interest in her. He tried to enlist quality men for the colony's churches and he sought more efficient supervision. Still, you can delegate some tasks but some can't be delegated.

In 1685, Compton recruited James Blair and sent him to Henrico. In 1687 Blair became "Commissary of Virginia." (A Commissary serves as a bishop's legal representative.) Blair worked hard to turn Virginia's religious situation around. He inspected churches, corrected ministers, corrected vestries and ably maintained communication with his Bishop. When Compton appointed Blair, fully half of Virginia's churches were vacant. In 1743, when Blair died, only two churches had no minister. Blair also got financial backing for a college in Virginia and in 1693 the College of William and Mary opened its doors.

The College of William and Mary began 70 years after Virginia's founding. Harvard began just six years after Massachusetts' founding. Located in Williamsburg, the College, with Blair as its first president, provided needed educational resources for Virginia's wealthy. Jefferson, Washington and other early American leaders and patriots studied there.

Just how successful was the Anglican church? by 1700, Virginia's Anglican membership stood at 5 percent of the population. Anglicanism never reached the "lower classes," but then most of the lower classes had little use for religion and among the rich religion is "what the proper man does." Colonial Anglicanism breathed an air of snobbery. Decent people are Anglicans!